Studies of the existing Maya writings show that they definitely were interested in prophecy and prediction of events relating to the human race. They based their predictions on a careful study of the movements of the planets, sun, moon and stars, which they believed were gods who could influence the daily lives of humans for good or for evil. They also believed, as revealed in their creation myths, that mankind has evolved through a series of progressively improved human races, or "worlds", which were destroyed in the past by cataclysms such as floods and earthquakes. Based on this evidence, it is possible that the Mayas believed that a large change was going to happen at the end of the Great Cycle, good or bad depending on the celestial influences. While scholars don't entirely agree on this issue, the few surviving Maya hieroglyphs and codices (Maya books) are mute on this point. But other interesting questions remain. Why did the Mayas follow the natural cycles with such great interest? Was it to predict the future, scientific interest or other reasons? What was the Great Cycle and what did this and other time periods mean to the Mayas?

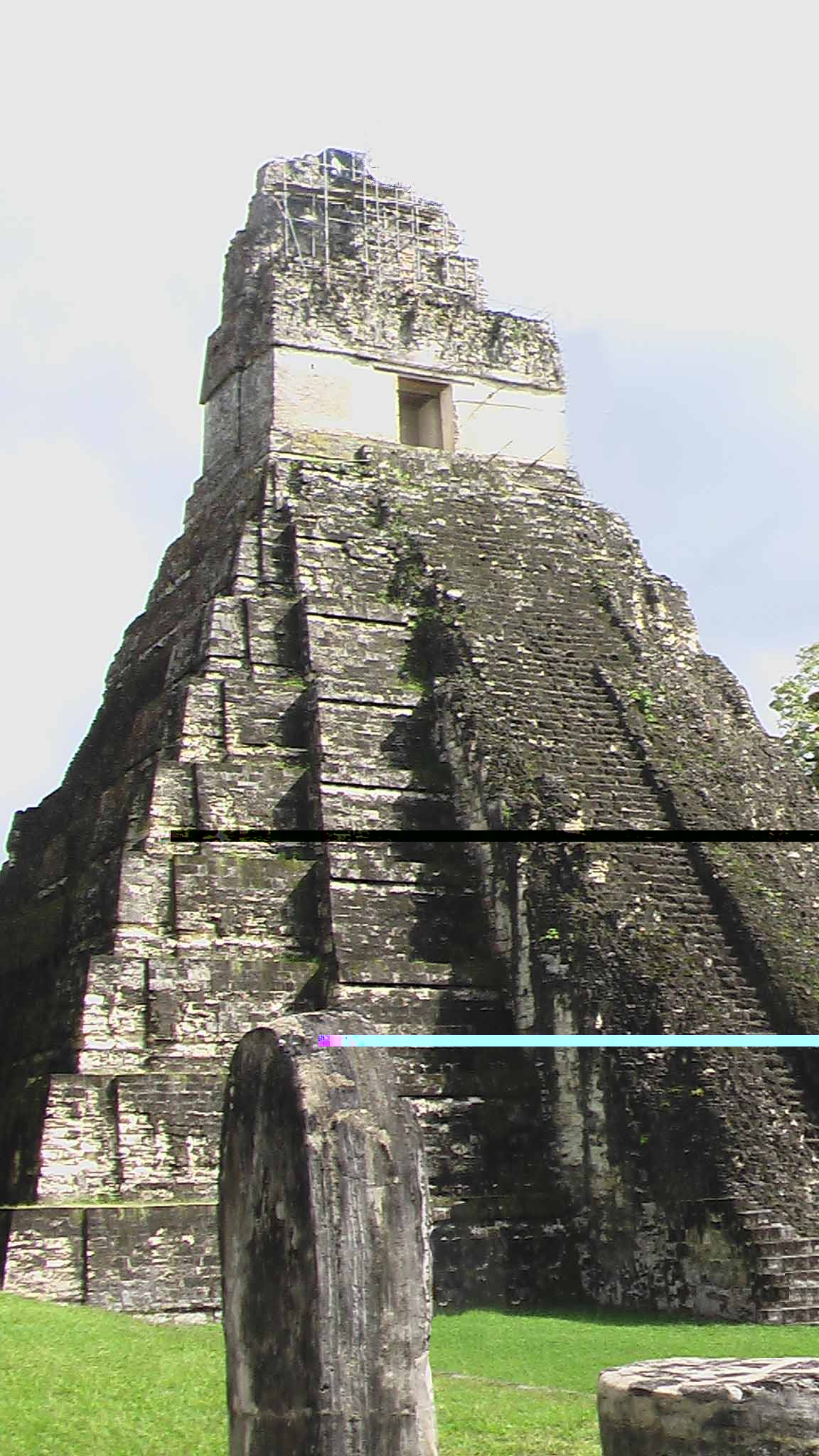

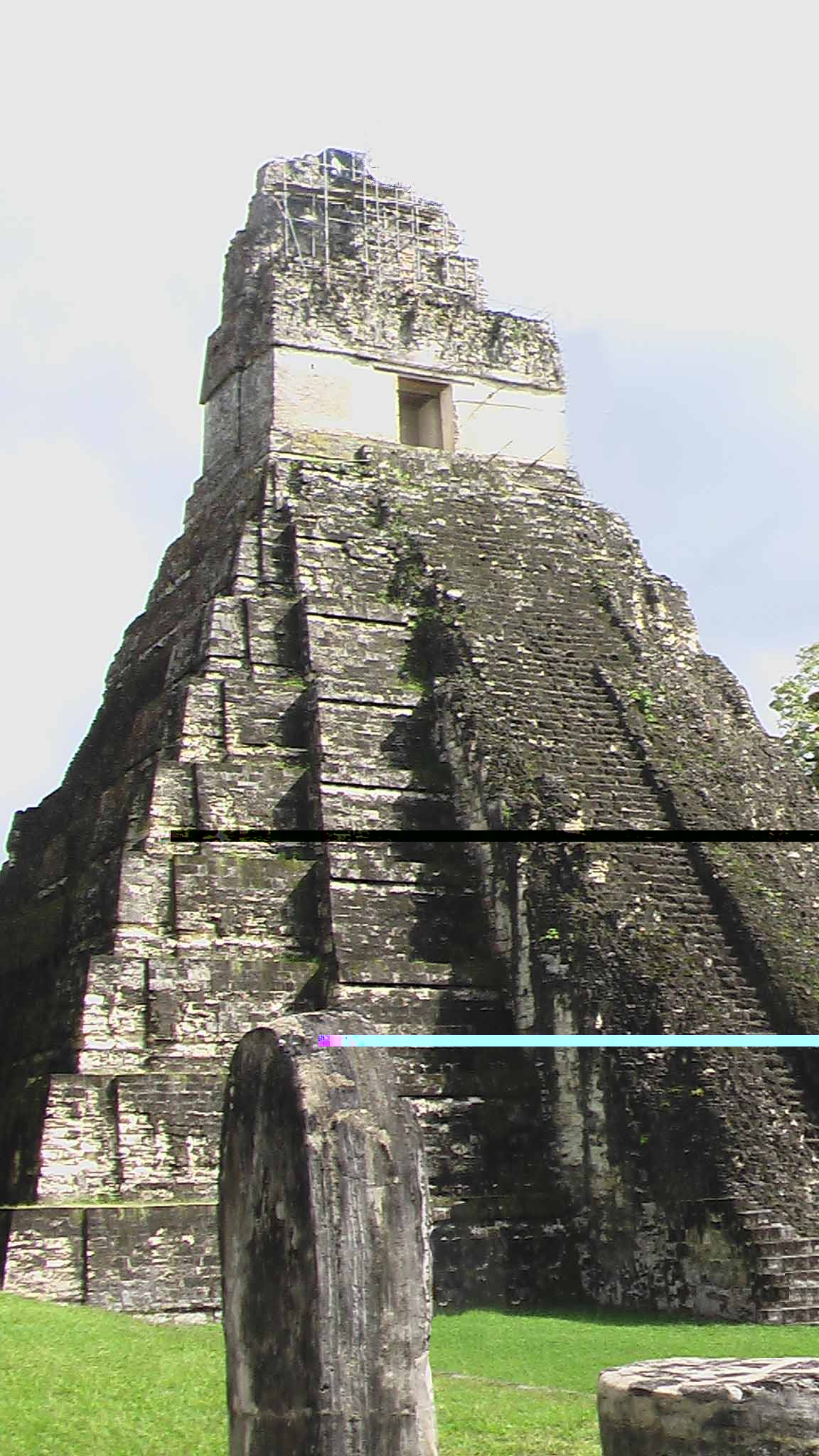

The Mayas flourished in Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala between 200 BC to 900 AD. The Great Cycle was one of many ways that they tracked the passing of time. They were extraordinary astronomers, who carefully observed the motions of the sun, moon, stars and planets, which allowed them to predict with a great deal of accuracy lunar and solar eclipses, the synodic period of Venus, and other astronomical events hundreds and even thousands of years in the past and future. They had several time periods that they measured and gave names to, as well as calendars they used to keep track of how many of these time periods had elapsed.

One cycle very important to the Mayas was called the "Tzolkin." This was a calendar made up by combining the numbers 1 through 13 with 20 named days. To run through all of the combinations of numbers and name days took 260 days. Another was the Ha'ab or vague year. This consisted of 18 named months of 20 days, with 5 days left over, for a total of 365 days. There was also the Calendar Round. This cycle is created by aligning the 20 name days and numbers 1 to 13 of the Tzolkin with the 18 named months of the Ha'ab aligned with the numbers 1 to 20. It takes 52 years for the same alignment of all four elements to recur, which is 52 years times 365 days = 18, 980 days. This calendar allowed the Mayas to uniquely identify a day 52 years in the past or future.

But the calendar pertinent to the Great Cycle is the Maya Long Count calendar. This calendar allowed the Mayas to count whole days accumulated from a date designated as day 0. With this method, they were able to uniquely identify a given day thousands of years in the past or in the future. The accumulations of time were based on units shown in the chart below. This chart was taken from Sylvanus Morley (An Introduction to the Study of the Maya Hieroglyphs, p. 62), a preeminent Maya scholar working in the early 1900's and Linda Schele (Forest of Kings, p. 81) working in the 1970's as one of the epigraphers who helped decipher the hieroglyphs. The chart shows how these scholars differ in their interpretations of how long the Great Cycle lasted:

1 Kin 1 day

20 Kins = 1 uinal 20 days

18 uinals= 1 tun 360 days

20 tun= 1 katun 7200 days (about 20 years)

20 katuns= 1 baktun 144,000 days (about 394 years)

Then, according to Linda Schele and others, next in the chart should be:

13 baktuns = 1 Great Cycle 1,872,000 days / 365 = approx. 5128 years

20 baktuns = 1 pictun 2,880,000 days / 365 = approx. 7890 years

But according to Morley:

20 baktuns = 1 Great Cycle 2,880,000 days / 365 = approx. 7890 years

As the chart shows, Morley argued that the Great Cycle was comprised of 20 baktuns. He based this on an analysis of how dates are written in the four surviving Maya codices. (For a detailed treatment of his logic, see pp. 107-111 of his book). Schele and others believe that though 20 baktuns do indeed make a Maya cycle called a pictun, the Great Cycle itself is only 13 baktuns long. They based this belief on how dates are written on stelae, or stone monuments, using Maya hieroglyphs (see Forest of Kings, p. 430). Thus, there is not full agreement among scholars as to the actual length of the Great Cycle. It is either 1,872,000 days (about 5128 years) or 2,880,000 days (about 7890 years) long.

Not only is there disagreement on the length of the Great Cycle, but not all Mayanists agree on the start date of the Great Cycle, the day designated as day 0 from which the Long Count began. The start date of the Great Cycle is derived from stelae found with hieroglyphs representing what the Mayas called the Initial Series. This was a starting date from which (almost) all other Maya Long Count dates were counted. (Morley on p. 61) cites two examples of hieroglyphs found that have other initial series). This start date in the Maya time keeping notation is called 13.0.0.0.0 4 Ahau 8 Cumku. The problem is determining what date this correlates to in the Julian or Gregorian calendar we use today. This involves analyzing the hieroglyphs and trying to correlate them to dates of known astronomical events, such as the conjunction of planets or eclipses, or to known historical events, such as the arrival of the Spanish in Central America. Based on analysis done by J. Eric Thompson, Joseph Goodman and Juan Martinez, three possible dates were identified:

11 August 3114 BC (Gregorian) 6 September 3114 BC (Julian)

12 August 3114 BC (Gregorian) 7 September 3114 BC (Julian)

13 August 3114 BC (Gregorian) 8 September 3114 BC (Julian)

The result is what is called the GMT correlation, after the three men who proposed the dates. Many researchers believe that the first date is the start date, while others, including noted Mayanists Linda Schele and Floyd Lounsbury, believe it is the last (they correspondingly believe that the Great Cycle ends on December 23, 2012).

Various Mayanists have speculated on why the Mayas chose this particular start date. Morley proposes that this date was selected as having "mythical significance" rather than historical significance (p. 61). He bases this idea on the fact that the date of August 11 (or 13) 3114 BC occurred at least 3000 years before the first time this date is actually found on stelae.

Others, such as Schele and Friedel (Code of Kings, p. 37) believe that this start date corresponds to the date of the creation of what the Mayas call the fourth world, which is the current world. This assumption is based on descriptions of that event found on Stela C at Quirugia, Guatamala. The Maya creation story is described in the Popul Vuh, a 17th-century document which relates the history of the ancient Quiche Indians as well as their creation myths. These myths say that so far man has lived in four worlds. The gods created the animals in the first world because they wanted a world of beings to honor and adore them. But these could not speak in one voice, so they were doomed to be sacrificed as the food of others. The gods tried again and created a second world, making a man of mud. But this man was too soft--he had no strength and blurred sight, and spoke but had no mind. So the gods broke apart the mud men and tried again. The third-world men were made of wood. But they had no souls or minds, and "did not remember their creator." The gods destroyed these by flood. Finally the hearth of the fourth world was created. The men of the fourth world were made of maize. They were much more satisfactory to the gods, as they had strength to walk on two feet, were able to talk and listen and had minds, intelligence and wisdom.

It is interesting to note that the Maya creation myth is remarkably similar to other Amerindian creation stories which say that the current human race is in either the fourth or fifth "world," with previous worlds destroyed by catastrophes. They are also similar to teachings about the creation of man and the universe given out in Egyptian, Babylonian, and Tibetan scriptures. We see another possible tie with Eastern teachings in the Hindu belief that the start of the current Iron Age, or Kali Yuga (see "Cycles" by William Q. Judge (http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/cycles/cy-wqj2.htm) for a general description of cycles and the Kali Yuga) began with the death of Krishna in 3102 BC, very close to the proposed start of the Maya Great Cycle. These are but a few examples of beliefs shared between cultures separated by wide differences in time and place. It makes one wonder if "The Light That Came from Across the Sea," as the Popul Vuh is also called, came from initiates who traveled from the east, or the old world, to the Americas, bringing the ancient wisdom with them.

If the beginning of the Great Cycle marked the creation date of the fourth world, then did the Mayas believe that the end of the Great Cycle marked the end of the fourth world, and the beginning of the fifth? Linda Schele thinks not: "In the near future Maya time also approaches one of its great benchmarks. December 23, 2012, will be 13.0.0.0.0 4 Ahau 8 Kankin, the day when the 13 baktuns will end and the Long Count cycles return to the symmetry of the beginning. The Maya, however, did not conceive this to be the end of this creation, as many have suggested. Pacal, the great king of Palenque, predicted in his inscriptions that the eightieth Calendar Round anniversary of his accession will be celebrated eight days after the first eight-thousand-year cycle in the Maya calendar ends. In our time system, this cycle will end on October 15, 4772" (Forest of Kings, p. 82). J. Eric Thompson says, however, when talking about the fact that the Maya seem more interested in the past than the future: "Apparently, the Maya, like the Aztec, believed the world would come to a sudden end, presumably when an overpowering combination of evil influences marked the termination of a time period" (p. 140). But he does not specify precisely in which time period the Mayas thought this would occur.

Morley also speculates (p. 32) that the last page of the Dresden Codex, one of four remaining Maya books, depicts the end of the world: "Toward the end of the Dresden Codex the numbers become greater and greater until, in the so-called 'serpent numbers,' a grand total of nearly twelve and a half million days (about thirty-four thousand years) is recorded again and again. In these well-nigh inconceivable periods all the smaller units may be regarded as coming at last to a more or less exact close… Finally, on the last page of the manuscript, is depicted the Destruction of the World, for which these highest numbers have paved the way." The destruction he describes is by flood, so one wonders if this is the Maya depiction of the end of the Third World, as described in the Popul Vuh.

The length of the Maya time periods followed a definite pattern and all had special meaning, as described by Schele and Friedel: The "endless succession of time was given order by grouping days into ever-repeating cycles ranging from the small to the inconceivably huge. Some of these cycles came from the observation of the natural world, for example, the cyclic movements of the moon, the planets, and the constellations. Others derived from the symmetries intrinsic to the numbers themselves, for example, the practice of counting in twenties. Other numbers and their repetitions were sacred and had magical properties" (p. 78) .

There are many examples of Maya cycles that are tied to celestial events. The kin, or day, is the rising and setting of the sun. The vague year, or Ha'ab, 365 days, is based on one orbit of the earth around the sun. The period of 5128 years, a postulated length of the Great Cycle, is very close to one fifth the length of the precession of the equinoxes, which is roughly 26,000 years. (And modern scholars are becoming more convinced that the Mayas were aware of the precession of the equinoxes, something they had repudiated in the past.)

There is also a recurrence of the numbers 13, 18 and 20. These and other numbers found in the calendars may be related to the nature of man himself. The use of 20 may, as Linda Schele speculates, represent the number of toes and fingers of a human. The 260 day Tzolkin cycle could represent the human gestation period. But many of the time periods are obviously multiples of previous time periods, which is significant in itself, as it showed that the Mayas believed that the core of natural law was repetitive and hierarchical. As Morley states, "all Maya periods, from the lowest to the highest known, are always in a continuous sequence, each returning into itself and beginning anew after completion. [This is] the most fundamental principle of Maya chronology--its absolute continuity throughout" (pp. 44-45).

The movements of the moon, sun and planets were so important to the Mayas that they regulated their daily and religious lives based on these cycles. This is evident from the numerous pages of synodic tables of Venus and lists of prophecies in the Dresden Codex and the Chilam Balam (the Maya book of prophecy. See the text of an English translation by Ralph L. Roys here: http:/www.mayaweb.nl/mayaweb/chilam.pdf). These cycles were tracked by the Mayas because they believed that the celestial bodies were inhabited by gods and that these gods could exert both positive and negative influences on the earth and its inhabitants. Thus, the positions of the celestial bodies relative to mankind influenced the daily life of man, so that at certain times of the day and year, as the planets and stars moved in the sky, these influences varied and changed. In this way certain days were more propitious for important events, such as marriage or going to war or planting crops. As Schele explains (Forest of Kings, p. 76): "The Maya saw stars and constellations, the planets and the moon, as living beings who interacted with the cycles, natural and social, of the Middleworld [the world of men]. To the ancient Maya the world of the stars was as alive as the world of humankind. Astronomical observation was not a matter of simple scientific curiosity, but a source of vital knowledge about Xibalba [the underworld] and its powers. Sky patterns reflected the actions and interactions of those gods, spirits, and ancestors with the livingbeings of the Middleworld. Both king and commoner adjusted their living to those patterns or suffered the consequences."

But many scholars believe that the Mayas' interest in planetary positions went beyond prophecy and fortune-telling. They point out that the Maya were deeply religious and sought to harmonize their lives with those of the gods. They believed that the characteristics possessed by the gods were also inherent to man's very being and that by studying the workings or laws of the gods, they could better understand the divine part of themselves. This would not only help them to become one with their divine source but would enable them to more wisely rule and predict the course of their own lives. They also believed, as revealed in the Popul Vuh, that the planets, such as Venus, were "bringers of light," celestial gods who were their spiritual teachers and providers of divine inspiration.

Thus, the debate continues about the meaning of the upcoming 2012. That the Mayas held the Great Cycle to be an important one is not in doubt, but many of their other calendars were also important to them in regulating their daily secular and spiritual lives. The Mayas do not directly say that the end of the Great Cycle signals the end of the world or ushers in a new spiritual age. It could be that to them it was the end of another era or milestone in the progression of time, just as we celebrate the end of each year and the end of the millennium. But they did believe in the cyclical nature of the universe and of human evolution, describing the rise and fall of the human race in the Popol Vuh as it evolved into self-awareness. So they may have believed that this race of men, this Fourth World, would end in a catastrophe as a result of overwhelming evil influences on man. It is difficult to tell: because the vast majority of Maya books and hieroglyphs have been destroyed the evidence in their own voice may have been lost. Certainly the Maya people living today place no great importance on the end of the Great Cycle. But as is shown by their fascination with celestial events, the Mayas were very much in touch with the natural world around them and sought to understand and live in harmony with the forces that drive the cycles of man and earth. In this way, they hoped to find their own divine source within, which perhaps could help them overcome evil influences and avert destruction.