Review Article

William Quan Judge (1851-1896) was one of the principal founders of the Theosophical Society, along with Helena Blavatsky and Henry Olcott. All three maintained that the Society grew from the efforts of a network of sages or spiritually-advanced teachers, some of whom communicated with and taught them and others. In 1894, three years after Blavatsky's death, Annie Besant formally charged Judge with misusing the handwriting and signatures of two of these sages in his correspondence, charges he denied absolutely. She further said that these very sages had told her to pursue this action. At that time Judge was Vice-President of the TS, head of its American Section, and co-head of its Esoteric Section; Besant was head of its European Section and co-head of the Esoteric Section. One official bringing a charge which, if upheld, would lead to the expulsion of the other was bound to cause conflict in the Society. In 1895 this Judge Case split the TS into two international organizations.

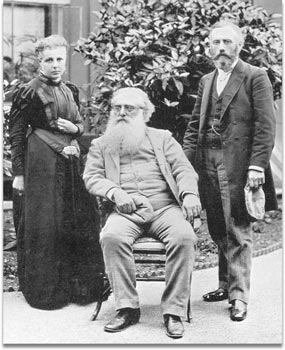

Annie Besant, H. S. Olcott, and W. Q. Judge in London after Blavatsky's death

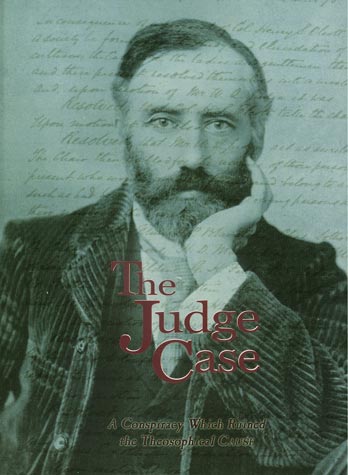

The Judge Case, a large-format book paged as two volumes in one [The Judge Case: A Conspiracy which Ruined the Theosophical Cause by Ernest E. Pelletier, Edmonton Theosophical Society, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, 2004; ISBN 0968160239, 71 photographs, 1,007 pages, hardcover, $95.00], brings together information and documents bearing on Judge and the Judge Case. It is not aimed at the general public, nor is it a tidy, predigested history. Rather, it is a resource for readers interested in exploring these events and coming to their own conclusions. It has a strong point of view, however, since the author undertook the work to vindicate Judge and try to restore his standing in the larger theosophical movement. [Interestingly, although an independent theosophical organization since 1995, the publisher, the Edmonton Theosophical Society, was from its inception in 1911 until 1992 part of the Theosophical Society that followed Annie Besant.]

Seeking "to present the issues, as they unfolded, by using direct quotations from as many original sources as possible" (1:xv), the author begins with over 300 pages of chronology in table form, containing quotes and their sources, in order to present the flow of events. Included are biographical sketches of forty prominent figures, also accessible through an index. Next an historical sketch by the author, over 100 pages long, narrates Judge's theosophical career, concentrating on various controversies. Part 2 contains documents organized into ten appendices covering such subjects as the Judge Case, the Prayag Letter, TS organizational history, and Judge's Diaries and Katherine Tingley. These articles, reports, letters, pamphlets, circulars, newspaper items, charters, etc., are not exhaustive. However, they give the reader access to a great deal of the material available to people when these events unfolded, as well as to private correspondence and later opinions of some of those involved.

But what is the value to us of this material, most of it more than a century old? Looking through The Judge Case, certain causes of the conflict stand out: personal differences, resentments, misunderstandings, and bad judgment; emphasis on communications and orders from occult sages, considered as authoritative; and, above all, a lack of generosity of spirit and brotherhood in the face of disagreements and accusations. In the end, it was this last factor that made it impossible for the Society to continue as one body.

It is always a challenge for people to cooperate, particularly in something they care about deeply. Supporters of causes inevitably differ about ideology, methods of organization, and means of achieving goals; they have their personal likes and dislikes, faults and blind spots. And everyone makes mistakes. With self-discipline and humility it is possible nonetheless to work together -- in the oneness of our hearts when we are outwardly divided -- in the case of the Theosophical Society, to form the nucleus of a universal brotherhood of humanity. Just as the sun shining on the ocean creates a path to it for each observer, wherever he may be and wherever he may move, so we can advance toward common goals along our own lines, while appreciating that others are contributing along theirs. If we find fault, let it be with ourselves and our own views and activities, rather than with others. By actively cultivating charity for all with malice toward none, eventually our actions and reactions will reflect compassion and lack self-righteousness even when we disagree, conflict, or part ways. For on the most fundamental level our fellow human beings are ourselves.

(From Sunrise magazine, August/September 2005; copyright © 2005 Theosophical University Press)

Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself. -- Leo Tolstoy